For Americans who live in cities or suburbs, going to the doctor is usually a simple errand. Even if they have trouble finding an appointment time that works for their schedule or getting their health insurance to cover it, their doctor’s office or hospital is usually a manageable distance from their home or work.

However, for 46 million Americans living in rural areas, accessing healthcare isn’t as easy. According to a 2018 survey by the Pew Research Center, nearly a quarter of rural Americans say access to good-quality hospitals and doctors is a challenge for their community. Making things worse, these rural residents tend to be older, less wealthy, and less likely to have health insurance than their urban and suburban counterparts.

The challenges preventing rural Americans from accessing medical care will likely worsen. The Association of American Medical Colleges projects a shortage of 54,100 to 139,000 doctors in the United States by 2033. Residents of rural communities will see their travel times to doctors and hospitals increase even more.

Of course, not every doctor’s visit requires in-person care: Telehealth is becoming more popular, thanks in part to government agencies offering grants and training programs promoting telehealth and the uptick in virtual visits during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021. However, many people in rural areas also lack access to a stable broadband internet connection—which renders telehealth visits nearly impossible.

To understand the effects of the rural doctor shortage in the United States, Incredible Health compiled data from government entities and research institutions. Here’s what you need to know about the current lack of medical care in rural communities, the effects the shortage has on patients, and the outlook for health care in rural areas.

Nearly 4 in 5 rural U.S. communities are short on medical staff

According to data from the Health Resources and Service Administration, 60% of the areas in the United States that are designated as “medically underserved”—meaning they face a shortage of primary care providers—are rural. Even more troubling, the average age of rural physicians is older, which means almost a quarter will likely retire by 2030. There has also been a decline in the number of medical school graduates who grew up in rural areas, who historically are more likely than their urban- and suburban-raised peers to practice medicine in rural areas as adults.

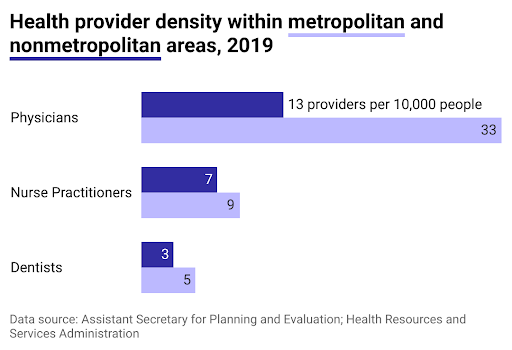

There are fewer health care providers per capita in nonmetropolitan areas

Although nearly 20% of the U.S. population lives in rural areas, less than 10% of U.S. doctors practice in rural areas. According to data from 2018 and 2019 that was released in 2021 by the Department of Health and Human Services, nonmetropolitan areas have fewer than half as many physicians per 10,000 people as metropolitan areas. Primary care providers and behavioral health care providers are in particularly short supply. For nursing shortages, the gap is slightly better, but there are still only seven nurse practitioners per 10,000 people in rural areas.

1 in 4 rural teens—and 1 in 5 rural adults—don’t have a primary care doctor who they see regularly

The lack of primary care physicians in rural populations is particularly troubling. Patients who regularly see a primary care physician tend to spend less time in the hospital and have lower health care costs over their lifetimes. Additionally, many Americans consider a primary care doctor a trusted source of advice: A 2022 survey reported that rural adults said that their health care provider was the most trustworthy source of information about the COVID-19 vaccine. Four percent of unvaccinated adults said that the reason they weren’t vaccinated is that they didn’t have a primary care provider.

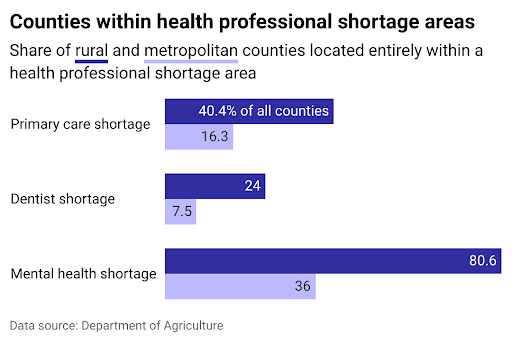

Compared to metropolitan areas, there are more than twice as many rural counties in health professional shortage areas

Data released in 2022 by the Department of Agriculture shows that rural counties are more likely to face shortages of primary care doctors, dentists, mental health care providers, and even hospitals.

Rural residents are also more likely to have to travel farther to access medical care. A 2018 report from the Pew Research Center found that rural residents drive 17 minutes on average to the nearest hospital—more than five minutes longer than the average driving times for suburban and urban residents. An extra five minutes might not sound like much, but it can make a big difference in a medical emergency.

Medical practices in the most rural locations treat four times as many Medicare patients as metropolitan practices

When a community has only a few health care providers, those practices end up with a much heavier workload. Research released in 2022 found that more isolated practices with fewer physicians cared for greater numbers of patients on Medicare. Practices in urban and suburban settings typically offer more flexible schedules, lighter workloads, and shorter shifts—an attractive proposition for new doctors.

142 rural hospitals have closed since 2010

Out of 185 rural hospitals that have closed since 2005, 76% closed after 2010. A 2022 study found that lower profits, shrinking patient volume, and staffing challenges contributed to most of these closures. Because rural hospitals typically treat more patients on Medicare and Medicaid, they often receive lower reimbursements than they would for patients with private insurance.

The patient mix in rural hospitals is also frequently older, poorer, and sicker than hospitals in urban or suburban settings. Making matters worse, when a rural hospital closes, it doesn’t just make it more difficult for residents of that community to get medical care—it can also harm the local economy by cutting physician and nursing jobs, as well as dozens of related jobs in the community ranging from food services to cleaning and transportation.

1 in 5 medical schools ran a formal rural program in 2019

Attracting recent medical school graduates to rural areas is crucial to reducing the rural doctor shortage. However, although most medical schools offered some rural clinical experience, only 21% of medical schools operated a formal rural program in 2019.

Rural training programs offer medical students hands-on experience in communities where a primary care doctor might be the only physician for miles, forcing them to expand their scope of practice to cover specialties like obstetrics. That expanded workload doesn’t translate into additional stress: One 2019 study found that rural physicians in South Dakota experienced lower rates of burnout than their peers in cities or suburbs.

Hundreds of millions of dollars are going toward mitigation efforts and solutions for this shortage

Addressing the rural doctor shortage will likely require a combination of several different approaches. Building on the existing rural training programs, the Department of Health and Human Services announced it would award more than $155 million to teaching health centers that focus on providing primary care and mental health care to underserved rural communities.

Creating pre-medical pipeline programs in rural communities can also help high school and college students see themselves entering medicine, which could bolster the rural applicant pool. The Office for the Advancement of Telehealth within the HRSA also runs several projects aimed at providing better access to telehealth services for rural communities.

Get job matches in your area + answers to all your nursing career questions